Other Nurserymen

Caldwell's was only one of many nursery businesses. Just how many we will probably never know as not all have left much of a trace. Sometimes a name pops up in a family notice, a report of a bankruptcy or in a news report. Perhaps a nurseryman won a prize at a flower show, or had something unfortunate happen at the nursery which made the news, or he appeared in a list of people on a jury.

Right across the north of England there were important nurserymen – Telfords of York; Pinkerton of Wigan; Perfect of Pontefract; Callender of Newcastle upon Tyne were just a few of the names from the 18th century. At the end of that century, the population was increasing as were the number of the wealthy middle classes who all had gardens that needed supplying, so the numbers of nursery and seed businesses increased. Here are the stories of just a few of those in Cheshire, Manchester and Liverpool, some of whom were Caldwell customers.

Bannerman, Alexander (c.1778-1827)

The name of Alexander Bannerman must have been well known because, when his son Charles set up in business in Manchester, he referred in his adverts to his 'late father'. Bannerman was born around 1778, married Ellen in 1805 and Charles was born in 1807, with his brother, another Alexander, seven years later in 1814. They lived at Walton on the Hill near Liverpool, where Bannerman had the Walton Nursery.

In 1812 Bannerman advertised his wide range of stock. For people who placed an order and wanted to take delivery in Liverpool, he arranged to be at Mrs. Collier's Seed Shop, near the top of Harrington-street, every Wednesday and Saturday from 12 o'clock until 2 o'clock. He also contracted to plant 'by the acre'. That same year he offered to buy as many acorns, hawthorn berries, holly berries, or any kind of tree seeds as this would- 'furnish employment for persons out of work, or the children of poor people; as the acorns and berries are easily found; and the price given will amply repay the gatherers for their trouble'. This meant that he could grow trees by the thousand and million – in 1818 he advertised that he had four million Larch Firs available for immediate planting. That same year a Mr. Henry Meadows was convicted of stealing willow plants from Bannerman's nursery. He was sentenced to six months' imprisonment.

At some point, Bannerman went into partnership with William Skirving, who continued to be an important nurseryman in Liverpool for many decades. Unfortunately Bannerman died as the result of a most dreadful accident. He and his servant were driving in a gig along the London Road from the Old Swan. When they reached the corner of Shaw's-brow (now William Brown Street) and Lime Street the horse was frightened by something. The gig hit the lamp-post on the corner and its passengers were flung violently against the old wall of the Alms-houses. Mr. Bannerman was taken to the Infirmary and later back home, but his head had been 'dreadfully shattered' and he died a few days later. He was only 49. His executors were quick to place an advertisement assuring everyone that the business would continue and all Mr. Bannerman's arrangements with suppliers would be honoured. His son Charles was only 19 when his father died, so the Trustees probably did not think he was old enough to take on the business and it was put in the hands of William Skirving.

Less than five months after his death a Bignonia capensis came into flower at Bannerman's nursery. It was thought to be the only one that had flowered outside of London. This plant, now called Tecoma capensis, is also known as the Red Cape Honeysuckle. It is not a real honeysuckle, but is a climber which has clusters of lovely red flowers. Bannerman would have been very proud of it.

Bannerman, Charles (1807-1857)

Following his father's death in 1827, Charles Bannerman journeyed to New Cross in Kent, where he joined the firm of Cormack, Son and Sinclair, staying there for three years. This was a nursery that had been in the Cormack family since the 18th century, but its name changed over time, so first it was known as Crombie and Cormack, then Cormack and Son, then Cormack, Son and Sinclair and finally Cormack, Son and Oliver. When Bannerman was there it was Cormack, Son and Sinclair. George Sinclair had been gardener to the Duke of Bedford, under whose direction he had undertaken research into grasses, he published the results in Hortus Gramineus Woburniensis. When Bannerman came back north and opened a seed shop in Deansgate, Manchester, his adverts usually mentioned this publication or simply 'the grasses recommended by Mr. Sinclair'.

Although Bannerman always advertised under his own name, perhaps he was supported by Cormacks. He must certainly have stayed in touch as when he left Manchester in 1839 his shop was taken over by Cormack, Son and Oliver and was run by Henry Dalgety Cormack. The Cormack nursery business was in trouble, though. Perhaps this next generation of Cormacks were not so skilled or perhaps it was because they started to lose their nurseries to development as London spread ever outwards. In 1849, Henry Cormack became bankrupt and the seedshop in Deansgate was taken on by another business – Dicksons of Chester.

Meanwhile, Charles Bannerman moved to Preston where he took over the seed shop that had been run by his younger brother Alexander. Charles died on 29 September 1857.

Bigland, Hodgson (1820-1896)

If you have ever read Elizabeth Gaskell's book Mary Barton, you will have come across Hodgson Bigland. He was just a young man when he left his home in Liverpool to set up a nursery in Moss Side, Manchester, but by the time he was 30 he was employing 39 men and 3 boys. In addition to the nursery, there was a shop in the Market Place in town, where sample plants were sent for people to view. In Mary Barton, Amy Carson accuses her brother of forgetting to ask Bigland for a new rose, and he replies that he did not forget but that even a very small one cost half a guinea.

In 1845 Bigland entered the competition to design the proposed Manchester parks which were paid for by a public subscription. The winning design was by Joshua Major of Leeds, but Bigland's designs came second and he won 25 guineas.

Bigland was a Quaker, so his movements can be easily tracked through their meticulous record-keeping. In 1855 his nursery had to close. The land was needed for development. He disposed of the seed shop to T.F. Winstanley of London and Thomas Crane, who had been Bigland's manager, later opened a seed shop of his own.

Meanwhile, Bigland left Manchester. He moved to near Birkenhead and started a business as an American Merchant. Later he moved to Darlington where he went to work at his wife's family's bank – Backhouse's (which later became part of Barclays). Jane Bigland was the sister of William Backhouse who was one of the original hybridisers of daffodils – at a time when they were not fashionable. Backhouse's daffodils, along with those of Edward Leeds, of Stretford, went on to be the parents of many of today's cultivars.

Bigland continued to work into his mid-70s. On 14 January 1896 he arrived at the Bank as usual, apparently as well as ever, but a few minutes later he fell unconscious and died. Although he had given up his nursery, he remained a keen gardener. In reporting his death, the newspapers said that he 'had a circle of devoted friends, and was much esteemed in private life. He was a great horticulturist, and took much pleasure in his hobby of gardening'.

Boardman, Giles (fl. 1780-1800)

Boardman's particular interest seems to have been fruit. In 1782 his nursery was at Pendleton, west of Manchester, where his fruit garden was a place with 'walks, bowers and pleasure ground' where customers could sit and receive refreshment while their orders for fruit were made up. In the 1790s these Fruit and Tea Gardens were run by John Boardman (possibly his brother) who started to provide music on Fridays, In July 1794 there was a special event on a Wednesday at which the Band of the Royal Manchester Volunteers played.

Meanwhile Giles had moved out to Barton-upon-Irwell where he set up an orchard. He ran into financial trouble and was made bankrupt, but somehow managed to hang on to the orchard. During the following century lots of Boardmans were nurserymen or gardeners in the area. There was another Giles and John Boardman, born around 1781 who were nurserymen at Barton on Irwell. They each had several children. Giles' two eldest sons were gardeners and in 1861 Richard Boardman was a nurseryman, occupying 16 acres and employing 7 men and 1 boy. Margaret Boardman, who was the wife of the John Boardman born about 1781, was gardening 3 acres with her three sons. Meanwhile a Miss Boardman was a fruiterer in King Street, Manchester. There was a John, born about 1831 and his brother Thomas (born c.1836) who were the sons of John (which John?; who knows!). They were both market gardeners and their brother Richard a domestic gardener. The Eccles home and garden of a Richard Boardman 'gardener and nurseryman' was advertised in 1830 after he died. It was only small (855 sq. yards) but contained two hot-houses planted with grapevines.

The original Giles Boardman owned John Evelyn's books: Sylva, Pomona and Kalendarium Hortense. These three, bound together with 'a full page manuscript discourse on the expense of planting and harvesting timber, signed at the King's Head Inn, Mar. 6, 1804 by Giles Boardman, Nurseryman' were sold some time ago. We wonder who owns them now.

Bowker, Joshua (c.1810-1886)

Joshua Bowker, the son of a farmer, was born around 1810 and, at the age of 30, was working as a gardener. By 1850 he was based on the Mottram Road in Hyde where he combined a nursery with The Grapes Inn and tea garden. The tea gardens were large and included, in addition to a number of pleasure seats, a large wooden building with room for up to 500 people and a place for a band.

Unfortunately, in 1853 Bowker was declared bankrupt and the business was auctioned, with the nursery plants being auctioned separately on 17-19 October. Bowker moved to Scarborough where he worked as a landscape gardener, and in 1866 he was again bankrupted. His son, Edward (born c. 1837) was also a landscape gardener, settling eventually in York, where Joshua died towards the end of 1886.

Bridgford, John (c. 1758-1825)

John Bridgford started his working life as a barber and a wig-maker, but by the 1790s wig-wearing was going out of fashion and it is probable that Bridgford was already a keen flower grower because he had a mid-life change of occupation. At first he combined the sale of seeds and bulbs with his hairdressing business and then by 1800, at the age of 42 he gave up hairdressing completely and two years later had his own nursery at Cheetwood. In December 1814, Manchester suffered more than a week of storms; slates and chimney pots fell and the roofs of partly completed houses lifted right off by the wind. Bridgford's hothouse was completely destroyed, but he managed to keep his greenhouse intact.

For a few months before he died, aged 67 in 1825, Bridgford served on the committee of the newly formed Manchester Floral and Horticultural Society. For a while his son Samuel continued the nursery, and three of his daughters ran his seed shop in town, but without success.

Butler, William (f. 1799-1816)

On 4 December, 1799, giving his address as the Hotel, Liverpool, William Butler penned an advertisement. He said he was an architect who could plan and build pineries, vineries, peacheries, green-houses and hot-houses heated by steam. He also undertook to plant forest trees 'by the acre'.

Just 2 months later he had acquired the nursery business of William Dickson, situated in Renshaw Street, Liverpool, and was advertising in both Chester and Manchester newspapers. He still offered to plan and execute improvements to land – plantations, pleasure grounds and gardens – and also to design and build all the necessary structures, but he also had all the plants, tools, etc that any gardener could need. His plant catalogues came complete with all sorts of information: when to sow seeds; what soil was needed for plants to thrive. He promised to add all new plants to his list – indeed he was just waiting for the weather to improve to take delivery of a new collection of Ericas and other plants from London.

Within four years, he had moved his nursery out to Prescot and his shop in town was in Church Street. In 1813 he ran a series of adverts in the region – including as far away as Lancaster – which listed his stock by numbers, including 3 million forest trees; 1 million thornquicks; more than 60,000 fruit trees; 50,000 shrubs; 10,000 American plants in pots; 3,000 plants for growing in hot-houses or green-houses. It is possible that Butler was already suffering financially because the catalogue he offered set out the plants in lots, suitable for any size garden from 100 acres downwards and he wanted 20% of the value of purchases with the order. The balance had to be paid when the goods were taken away – which the purchaser had to arrange at his own expense.

On Wednesdays and Saturdays, Butler was at his shop in Liverpool; on Tuesdays he could be found at the Coach and Horses Inn, Deansgate, Manchester and on the first Monday in the month, during the planting season, at the Feathers Inn in Chester.

Despite his large and varied stock and his aggressive selling, Butler was declared Bankrupt in 1815 and over the next couple of years his properties were sold off to meet his debts. He somehow managed to continue the nursery, but he died in 1817 and it was his brother James who advertised that he had taken over the nursery and was wishing to reduce it in size. He had 'large quantities' of apples, plums, pears and cherries plus a variety of trees from 3ft to 12ft high.

Although it looked as if the nursery was going to fail, James was able to turn it around. Losing all connection with William's business (and his debts), he was able to raise the money to buy the remaining stock, and made a lease agreement with the Earl of Derby who owned the land. What happened to James we don't know, but the Prescot nurseries continued to thrive under a succession of new owners. In 1870 George Davies left his Green Lane nursery and moved to the much more extensive Prescot nursery.

Capstick, Joseph (fl. 1830s)

In 1830, Capstick, describing himself as a 'Nursery, Seedsman and Florist', based at 85 Deansgate, imported a chest of bulbs from Holland, including 'Amaryllis, Hyacinths, Narcissus, Tulips, Anemonies, Ranunculus, Jonquils, Irises, Ixias, Crocuses, Crown Imperials' and also had for sale, fruit and forest trees and ornamental shrubs.

His purchases from Caldwell's were considerable – in the second six months of 1833 alone he placed 15 orders totalling £57 13s 10d. A careful examination of the receipts and payments book for 1832-1849 will show to what extent he paid for goods purchased, but it is likely that many, if not all, his purchases remained unpaid for. In 1838 at a hearing of his bankruptcy it was reported that 'Capstick's case was a very bad one, and unopposed, he had sold all his property, and had not divided a single penny amongst his creditors'.

Cunningham, George (c.1757-1836) and Cunningham, George (1800-1890)

In 1831 John Loudon described George Cunningham as 'the father of Liverpool grape-growers', who had been growing grapes for half a century. At the time, George senior was well into his 70s. He lived at West Derby in Liverpool and his nearby nursery was called Oak Vale. He and his son, who followed him as nurseryman, have left a mark on the area. A cul-de-sac is called Oak Vale (perhaps on the very site of the nursery) and nearby is Cunningham Road.

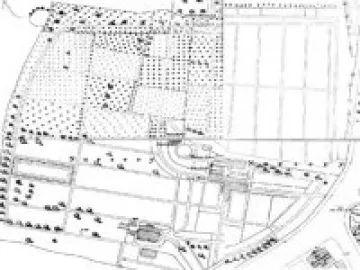

In addition to the Oak Vale Nursery (and a seed shop in Paradise Street in the centre of Liverpool), Cunningham had a nursery in Hulme, Manchester – perhaps the one owned by McNiven and Thorley, that Mary Thorley had put up for sale following the death of her husband. It was quite a big site, alongside the Chester Road, and in the same year that he wrote of Cunningham senior's grape growing it was visited by John Loudon who said that it was 'remarkably well laid out, and highly kept'. The map below was drawn more than 10 years after Loudon's visit, by which time Cunningham had taken William Orr into partnership.

Cunningham and Orrs nursery at Hulme.

Probably Cunningham junior had run this nursery while his father was alive, but had returned to Liverpool to run the Oak Vale nursery following his death, leaving Orr in charge in Hulme. Unfortunately the same fate which befell Bigland's nursery befell this one. The town had been spreading inexorably outwards. Not only was the pressure on land for housing becoming acute, the nurseries were suffering from the effects of smoke. Particularly damaging was the smoke from brick-kilns, and there were some within some fifty or sixty yards. It was almost impossible for trees to thrive in such conditions, so in 1854, when the lease had run out, the 10 or so acres that the nursery covered went for building. After Cunningham & Orr's closed, Orr continued to work as a nurseryman from a site in Northumberland Road. Like so many nurserymen, Orr was a Scot. He was born around 1788 and died, probably, in 1869.

The Oak Vale nursery in West Derby continued to thrive and in 1848 a new Rhododendron – R. cinnamomeum cunninghamii – that had been grown on the nursery was launched. It was described by Joseph Paxton as 'probably the best hybrid Rhododendron yet raised'. Cunningham explained that he had been trying to achieve a hardy rhododendron with pure white flowers which retained the purple spotting of one of its parents. Too many rhododendrons, he said were ruined by the frosts in Lancashire. (Rhododendron 'Cunningham's White', which is still available today, seems to be a different plant, raised by James Cunningham of Comely Bank nursery, near Edinburgh.)

Paxton's Flower Garden, 1850-51. Courtesy books.google.com

Cunningham supplied many plants to the Botanic Nursery in Dublin and in 1840 a book about the insects infesting the flower garden described Camellias, listing 35 by name most of which, it said, could be obtained from Cunningham's of Liverpool.

Following George junior's death, his Oak Vale Nursery suffered the same fate as the Hulme nursery – the eleven acres on which it stood went to development and a four-day auction was held to sell off all the stock.

Dickson's of Chester (1820-1933)

So many members of the Dickson family were involved in nursery work that it can be difficult to work out their exact relationships. The two Dicksons who opened a nursery at Bache Pool in Chester in 1820 were cousins – James and Francis. Francis (born on Christmas Day, 1793) was the youngest son of the Dickson who had the nursery at Leith Walk, Edinburgh. He had trained at the famous Malcolm's nursery in Surrey.

There was an Archibald Dickson at Hassenedeanburn, near Hawick in the Scottish Borders, and that may explain why they ended up in Chester. In 1818 the Hassendeanburn nursery had supplied more than half a million trees to Henry Potts of Chester for planting on his land in Wales. Perhaps Francis and James were relatives of Archibald, had come down to oversee the planting and decided to stay.

They occupied the ground at Bache Pool for nearly two decades before moving to nurseries at Newton and Upton. Although based in Chester, they advertised in Manchester and after the bankruptcy of Henry Cormack, took over the shop at 106 Deansgate. Each of the cousins had married and raised a family, so each had a son to join him in the business. This meant that in 1853 they ended their partnership, each going into business with their respective son. James retained the shop in Deansgate, while Francis opened another at 14 Corporation Street.

Likewise, in Chester, they occupied two separate shops in Eastgate Street – James at 102 and Francis at 106. It could not have been easy, suddenly being in competition with each other. In Manchester, Francis described himself as the 'senior partner of the late firm, a practical nurseryman of 40 years' experience', while James responded that he had 'for thirty-five years been sole managing partner of the seed concerns, both at Chester and Manchester'.

Francis died on 3 March 1866 and warranted a considerable obituary. He had been a friend of John Loudon, who often consulted him when writing his many books. In 1825 he was nominated, by Thomas Andrew Knight, to be a corresponding member of the Royal Horticultural Society. Francis liked the challenge of growing those plants considered the most difficult; he was known for his integrity, warm-heartedness and generous hospitality. His two sons, Francis Arthur and Thomas took over the business.

James died on 28 December 1867 and likewise was succeeded by his sons. The two firms continued to operate separately until, by the time Francis Arthur died, they had amalgamated. The families had prospered and Francis Arthur's obituary (in 1888) dwelt more on his contribution to the running of Chester (he had been an Alderman and Mayor) than on his horticultural abilities.

The firm continued to operate well into the 20th century. In 1918 the Chester Horticultural College was set up,'to increase the number of efficient women, and thereby to increase the food supply'. The tuition was given at Dickson's nurseries which then covered an enormous 530 acres.

The nurseries closed in 1933.

Diggles, Thomas (c.1794-1855)

Before setting up as a Landscape Gardener in 1838, Thomas Diggles had been Head Gardener to Rev J Clowes of Broughton Hall for sixteen years. He was born in Prestwich and lived in Broughton. In 1851 he lived at Singleton Brook Cottage which was next door to Park Nursery, run by William Lodge.

In 1845, Diggles came third in the competition to design the proposed Manchester public parks and in June 1850 he was one of the judges at the Manchester Botanical and Horticultural Exhibition. In 1849, Diggles announced that 'in deference to the urgent requests of many gentlemen' he had taken a licence to appraise garden and nursery stock. He died on 6 November, 1855, aged 61.

Faulkner, James (1797-1865)

Born in Didsbury, James Faulkner's first nursery was in Smedley Lane, north Manchester although by 1846 he was established at Kersal Moor – perhaps in the same nursery that Robert Turner had run the previous century. When John Loudon went on his Gardening Tour of Britain, Faulkner's was one of the nurseries he visited when he reached Manchester.

Like William Lodge, Faulkner was a keen plantsman and won lots of prizes at flower shows, eventually becoming a show judge. In 1833, The Manchester Times carried a report: 'The admirers of flowers will be highly gratified by a visit to Mr. Faulkner's gardens at Smedley. That very rare and curious plant the Lady's Slipper, in a great variety of shades, is now nearly in full bloom, and supposed to be the finest ever seen'.

In addition to his nurseries, Faulkner ran a fruit shop at 67 Long Millgate in the centre of Manchester. He died at his nursery on 27 February 1865. The notice of is death said that he was a 'horticulturist, lamented and respected by all who knew him'.

Hamnett, James (c.1796-?)

James Hamnett was a Caldwell customer. He was born around 1796 and was married to Ann. They lived almost next door to Richard Smalley Yates. Hamnett occupied eight separate plots of land in Sale alongside what is now the main A56 road between Manchester and Altrincham.

Lodge, William (c.1805-1855)

Born in Uley, Gloucestershire around 1805, Lodge moved to Manchester and married his Salford-born wife Mary. They had seven children who all helped in the two nurseries – one was in Broughton Lane, the other at Singleton Brook. In 1905 Louis Hayes wrote a book called Reminiscences of Manchester from the Year 1840, and he recalled the Broughton Lane nursery well:

'Broughton lane had its hedgerows thick with hawthorns and wild flowers peeping out from beneath with gay profusion whilst the gardens about were gay with bloom. A few yards down the lane you came to Lodge's Nursery Gardens, approached by a long, wide pathway, and bordered by a small running brook. Inside the Nurseries there was an extensive orchard of pear, apple and plum trees. Scattered about were summerhouses and arbours, where people could sit and have their tea, with water-cress. In the spring time it was quite a sight to stand on the higher ground on Bury New Road, and look across to Lodge's Gardens, at the wide expanse of fruit trees laden with bloom.'

Lodge was a keen plantsman and won many prizes at local shows, not just in Manchester, but also at Oldham, Altrincham and Ashton. Although his business was a general nursery, he was at heart a florist and most of his prizes were for florists' flowers. He was particularly successful with dahlias. Unfortunately he died in 1855 aged only 50. His family kept the nurseries going for a while, but the demand for housing in the ever-expanding town meant that the land eventually went for development.

McNiven, Charles (d. 1815) and Peter (c.1738-1818)

We are not sure when Charles and Peter McNiven arrived in Manchester and set up in business. Peter was the gardener and Charles a surveyor. They don't appear in the 1772 Directory, but they were certainly there in 1775. Their original nursery was in Deansgate – then known as Alport Lane – and perhaps they had one of the plots on Humphrey's gardens, a very popular place on fine Sunday mornings in 18th century Manchester where people went to admire the growing plants and purchase salads and bunches of flowers. The gardens were sub-divided into 20 plots and let on fifteen year leases in 1770.

Nearby worked James Ratchford, a gardener if not a nurseryman. In 1784 he advertised that he had brought from Africa the seed of a new cucumber, prickly, green but covered with a white powder, with a long stalk and the 'best and earliest kind ever seen in the Kingdom'. In Manchester it was only available from Mr. Ratchford and 'Messrs. McNivens, nursery and seedsmen'. In the 1790s McNivens bought plants from both Caldwell at Knowsley and Nickson & Carr at Knutsford.

In 1796, the company had problems with one of its employees. Joseph Roberts, who took care of the shop, living on the premises, absconded, taking with him the Nursery Books and all the orders which had been received. Peter McNiven had to place an advertisement warning customers not to settle any accounts with him!

Peter McNiven was born c. 1738, so he was already middle-aged by the time he can be positively placed in Manchester, which is 1775, but he lived to the age of 80, dying on 9th January 1818 'much respected'. Ten years before that, having moved the nursery out to Hulme, he took William Thorley into partnership. After Thorley's death around 1824, the nursery was run for a while by Mary Thorley.

Noyes, Charles (c.1800-1871); Charles James (1846-1920); Charles Stafford (1882-1995)

Charles Noyes was born in Andover, Hampshire around 1800. He was married to Susannah, from Sandy, Bedfordshire, but by the late 1830s they had settled in Pendleton, living at 30 Eccles Old Road and running the Hope Nursery in Sandy Lane. Theirs was another dynastic nursery family which was successful for at least 100 years. The firm appears in a Directory of 1933.

After Charles died in 1871, he was succeeded by Charles James and was followed in due course by Charles Stafford. Charles Stafford's middle name was his mother's surname. Charles James married Annie Mary Stafford whose father, Thomas, was a Horticultural Salesman. Thomas' father was Samuel Stafford, the well-known Hyde nurseryman.

Charles exhibited and won prizes at the Manchester Botanical and Horticultural Society shows and in 1857 he created the crown of flowers which was hung over the entrance to the Patricroft railway station when Queen Victoria arrived for her visit to the towns to open the Exhibition of Art Treasures . She stayed at Worsley Hall. (Charles must have been very proud – newspapers all round the country carried the information, including his name.)

Raffald, John (c.1736-1816)

At one time, John Raffald was head gardener at Arley Hall, where he met his future wife, Elizabeth, who was the housekeeper there. When they married, they moved to Manchester where Elizabeth became a very successful businesswoman and the author of a book on cookery, which was first published in 1769. John Raffald had two brothers, James and George, who were also gardeners, and they sold plants in the Manchester market. Elizabeth had a confectionery shop and eventually one of her nephews, James Middlewood, combined the confectionery and nursery business in his shop in St Ann's Square, Manchester.

John Raffald gave up the seed business and became the landlord of a pub, The King's Head, in Salford. In August 1774 he hosted a Carnation Feast. He seems to have run into money troubles, though. In 1779 he began a new career at the Exchange Coffee House, but after Elizabeth's death in 1781 he left Manchester. He must have returned, because in 1796 he disappeared from his home in Salford and a notice was put in the paper. He was described as 'a stout built man, dark complexion, about 5 feet 9 inches high, upwards of 60 years old, and walks rather lame'.

While Elizabeth lived, she was in charge; John was reckoned to be charming but a bit feckless. He had a habit of threatening suicide, but Elizabeth found an effective way to stop him moaning. One day, having spent all morning in bed he announced he would drown himself, Elizabeth said 'Well, I'll tell you what, John Raffald; I do think it would be the best step you could take; for then you would be relieved from all your troubles and anxieties, and you really do harass me very much'. He never threatened it again!

Shaw, John (1814-1890)

For half a century John Shaw was a prominent person in horticultural circles and he was a Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society. He was born in Dumfries, Scotland, and eventually moved to Manchester where he had the Whalley Nursery in Moss Side. In 1851 he employed eighteen men and two apprentices. In February 1859 he opened the Stamford nursery in Bowdon almost opposite Dunham Park. He threw a party and planted two deodar cedars to mark the event.

Shaw was a Landscape Gardener as well as a nurseryman and designed Stamford Park in Altrincham with the actual construction being undertaken by his son, John Shaw, Jr. The park was a series of circles and ovals, providing space for cricket, football, bowls, quoits, and children's playgrounds. Enclosed by trees was a lake, for swimming. In October 1880, the park was opened. A procession, complete with brass band, made a circuit of the town, ending up at the gates to the park. Shaw presented a gold key to the mayor, who unlocked the gates, made a tour of the ground and declared the park open to the public.

Like other nurserymen, Shaw exhibited at flower shows – not always for competition. At the Botanic Gardens Extra Flower Show (June 1853), he provided a display of ericas and 'a Quercus niger, a new variety of oak', considered by the judges worthy of a certificate of merit. In 1864 he displayed roses at the first exhibition held by the Sale and Ashton-on-Mersey Floral and Horticultural Society. He won several prizes at the Grand National Horticultural Exhibition held at Manchester in May, 1869 – they were for roses; orchids; stove and greenhouse plants in flower; miscellaneous plants; Dracænas or Cordylines; pair of palms; pair of pyramidal bay trees; twenty-four hardy ferns; ten amaryllis in flower; twelve hardy rhododendrons in flower and twelve hardy azaleas in flower, although his only first prize was for twenty hardy conifers. In 1872, he was a judge at the September show held at the Manchester Botanic Gardens, where he received two first-class certificates for new plants – one was a Geonoma (a type of palm) and the other a Musa superba (today known as Ensete superbum) – and a first-class commendation for a miscellaneous group of plants. Two years later he received a first-class certificate for another new palm.

Shaw developed a new form of labels made of polished zinc. The names of plants were deeply etched in the metal and then the names were filled with a black substance. These were approved by the Royal Horticultural Society – as long as the black substance was permanent and the polished surface did not become tarnished.

Following his father's death at the age of 78, John Shaw, Jr, continued in the business until at least 1923.

Slater, John (c. 1799-1883)

John Slater was a contemporary of James Faulkner and just as keen on his plants, but he never gave up his job as a brush-maker even though he also sold florists' flowers. He was still in his teens when he began growing them, but rather than run a nursery full-time, he wanted to make sure that others could share in his passion. So he started writing articles for various magazines and then in 1843 wrote a book, to help young amateurs, on how to grow tulips, which were his particular passion. Slater never forgot the difficulties of the young and impoverished, but nevertheless keen, grower and did his best always to support them. In 1852 he started his own monthly magazine (The Floricultural Review and Florists' Register), which he sold for just twopence an issue (compare this with the weekly Gardeners' Chronicle which cost sixpence, Joseph Paxton's monthly Flower Garden which was two shillings and sixpence and the quarterly Horticultural Society's Journal, a whopping five shillings). His book The Amateur Florist's Guide, published in 1860, was sold for just two shillings. A review for this book said that 'Mr. Slater is an experienced cultivator and a good judge, and a not wearisome, but most agreeable and explicit writer'.

Slater's enthusiasm sometimes led him to enter into long arguments in magazines. One such was with Mr. Walker of Winton. Their argument in the Midland Florist magazine was finally stopped by the editor who said that 'enough has been said on the subject'.

Slater was in great demand as a show judge and was also secretary to both the Oldham and Ashton Floral and Horticultural Societies. In 1851, the Oldham Society presented Slater with a piece of plate 'as a mark of respect for his persevering exertions in promoting the science' and when this was reported in The Cottage Gardener he was described as 'one of the most energetic florists in the north ... a warm-hearted as well as a warm-headed florist'.

Stafford, Samuel (c.1795-1869)

Samuel Stafford's nursery was in Hyde, but he had a market stall in Manchester. He was born in Gee Cross, Cheshire and the Hyde nursery was in business from around 1830. In 1851 he employed 20 men. His family also worked in the nursery and his grand-daughter married Charles James Noyes.

In 1864 The Floral World and Garden Guide described Stafford's catalogues as of 'more than average interest and merit ... neither voluminous nor verbose, but short, concise, and containing only the choicest and most useful subjects...'

Stafford went to many flower shows – Glossop, Ashton, Oldham, Manchester, Rochdale – sometimes displaying plants and sometimes being a judge. In 1857 in Oldham, he provided a 160 foot display of greenhouse plants at Greenacres Grammar School, to mark Queen Victoria's visit to the Art Treasures Exhibition in Manchester.

Following his death, (7 May, 1869) his son Samuel continued in the same business until after the turn of the century.

Taylor (d. 1820) and Smith (c.1763-1852)

Although their nursery was in Dukinfield, around 1808 Taylor and Smith opened a seed shop at 32 Deansgate, Manchester. Taylor died around the end of 1820 and Smith left Dukinfield for Flixton. This appears to have been due to a disagreement at the Chapel that Smith attended. Smith's daughter married Robert Moffat who had come from Scotland to work in the nursery and the two became missionaries in Africa. His son John became a minister and worked in Hulme before leaving for India.

Meanwhile, Smith continued at his Flixton nursery until, around 1839 he decided it was time to retire – he was in his mid-70s by then, having been born in Scotland around 1763. Whether or not he managed to sell his nursery is not known, but at the 1851 census, when he was around 87, he was still referred to as a nurseryman.

Turner, Robert (c. 1705-1787)

Robert Turner may have been the first Manchester nurseryman and was certainly the only horticulturist to be recorded as a nurseryman in the first Manchester Directory published by Mrs. Raffald (see John Raffald) in 1772 . Turner's nursery was at Kersal Moor, to the north of the town. It was a favourite place for people to gather and for many years horse races were held there. The earliest advertisement for Turner's nursery that has been found is dated October 1755.

So it was probably Turner that the new Bishop of Man (John Hiddesley) was referring to when he sent a letter to his friend John Byrom in November 1755:

'If the Manchester nursery-man (whose name I know not) will venture to trust the Bp. of Man (whose name he is probably no less a stranger to) for a certain portion of his vegetable family, he may transmit as under, at such time and season of the year as he shall judge most proper: --

12 Yews of about three feet high.

6 Laurustinas.

6 French or good baking Pippins, for standards.

6 Apples of good hardy sort, for espalias.

12 Scarlet double Hollyhocks, (no other colour.)

18 Honeysuckles, of the hardiest kind.

24 Province or Cabbage Roses, (no other sorts.)

He will be pleased to pack 'em carefully in mats, and direct them for the Bp. of Man, to the care of Captain Kennish at Liverpool.

If he could procure intelligence when the vessels trading to this isle are likely to come off, there would be less hazard of their laying too long out of the ground.'

Later advertisements show that he had an outlet in Manchester and in 1777 a lengthy advert concluded 'I have followed Nursery Business about 50 years here on my own Account'. He was still advertising 10 years later.